Dissecting the interstellar medium of a distant galaxy

In this study we have studied the cold

in a distant galaxy — cold

in this case refers to temperatures around 100 degrees Kelvin where the gas is mostly neutral and molecular. This cold gas is essential for the evolution of galaxies as it serves as the direct reservoir for star formation. The cold gas phase is very difficult to observe directly at large cosmological distances and in this particular study we have used a lucky alignment of galaxies and a background quasar. (A quasar is a super massive black hole which accretes matter onto it and in turn releases a a lot of gravitational energy. This energy release causes the surrounding gas an extremely luminous emission of light.)

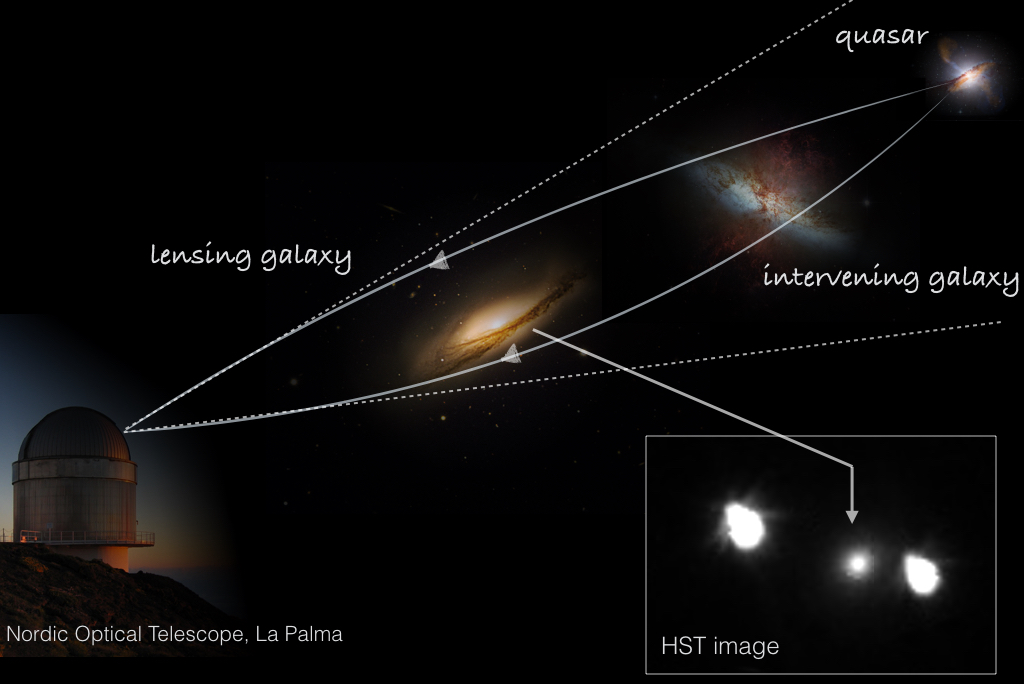

We observe a phenomenon called gravitational lensing caused by the warping of space-time around massive galaxies.

In this case, there is a very massive galaxy (the lensing galaxy) in front of the distant quasar. The gravitational field from this galaxy causes

the light from the background quasar to bend. Because of this bending of the light, we see parts of the quasar's light

that would otherwise not reach the Earth. I've indicated how this looks in actual data from the Hubble Space Telescope

(in the lower right corner). Here we see two images of the background quasar (the two bright spots) and between the

two images we see the lensing galaxy.

What makes this system even more interesting is the fact that there is a second galaxy located between the lensing galaxy and the

background quasar. We do not directly see this intervening galaxy in the image from the Hubble Space Telescope

because it's extremely far away and very faint. However, we can infer it's existence due to the fact that some light

is missing in the light from the quasar. This missing light has been absorbed by atoms and molecules in the intervening galaxy.

Thanks to our understanding of atomic physics we can count the number of different atoms and molecules in this distant

galaxy based on the fraction of light that is absorbed away. And all of this is possible even though we don't actually

see the light from the intervening galaxy.

The article is published in the scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics

Also available for free at arXiv.org.