Missing photons reveal galaxies hiding in the dark

My new article is out and if you feel like learning something about galaxies then read on. I've tried to put together a friendly illustration for the not so ultra geeky people out there.

I love studying galaxies, especially very distant ones! And one of my favorite ways of doing so is a slightly backwards approach compared to what most people might think galaxies and astronomy in general. Most of the time I don't even really see the galaxies that I study... So how does this work? Let's take a few steps back and look at what a galaxy is.

When I say a galaxy

, most of you probably think of a huge collection of stars shining in the sky, just like the Milky Way (our own galaxy) can be seen as a white hazy band of star light all blended together. You might also think of the amazing photographs of nearby galaxies with their complex spiral patterns and vivid specks of color. And you're right, those are galaxies! But galaxies are much more than that. Those colorful regions you see in pictures of galaxies are not stars, but actually gas bubbles glowing at very particular wavelengths, thereby giving rise to the characteristic colors. The color depends on the composition of various atoms in the gas; oxygen atoms, for instance, emit green light at a wavelength of roughly 500 nm.

So galaxies are not just a big collection of stars, they also have vast amounts of gas (at least at early times in the Universe, that's a whole other story), this is what we call interstellar gas

— it's literally in-between the stars. But a lot of the gas in galaxies does not shine at wavelengths that our eyes can see, and it can therefore be very hard to study this gas directly. And as it turns out, the interstellar gas is extremely important for the evolution of galaxies since new stars are formed out of this interstellar gas. So in order to fully understand the galactic ecosystem and how it evolves over time we need to study all its components.

Looking at the light from stars and gas is what we call emission studies

of galaxies. We can look at the amount of light we receive and figure out how many stars are needed to produce that light, how massive they are, and even how old they are. But just as a bright lighthouse at the shore cannot be seen until you get close enough, the galaxies that are very far away cannot be seen because their light is too faint to reach our telescopes here on Earth. The farther we look away, the harder it gets to see the smaller and less luminous galaxies.

This is where my backwards approach

comes in handy. As I mentioned earlier, the atoms in the gas can emit light at very specific wavelengths, but they can also absorb light at these same specific wavelengths. This means that if a bright source is shining through a bubble of gas, we can see that there is some gas there, because some of the light from the background source at those specific wavelengths is "missing". We can also measure how much gas is there, and thanks to very precise measurements from instruments at the Very Large Telescope in Chile we can even measure the gas temperature and density.

So instead of looking at the light emitted from stars and gas in the galaxies, we can look for bright objects behind the galaxies and see that some light is missing. The galaxy in the foreground has absorbed some of the light, and this tells people like me that there's something to be found here, even if we cannot see the light from the galaxy.

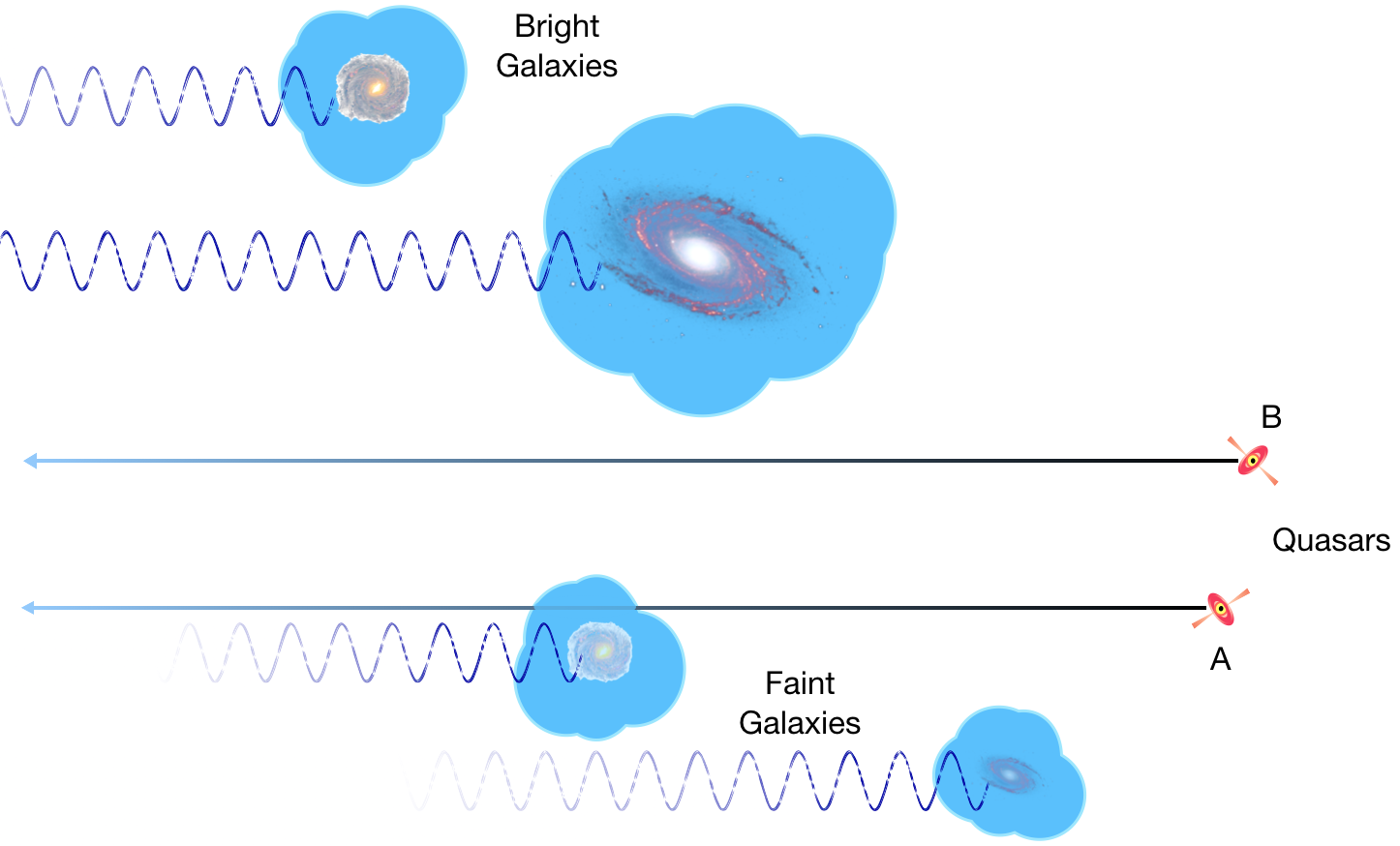

I've illustrated this in the figure below. The galaxies are living inside their atmospheres

(blue shaded clouds) of gas which reaches beyond the region where most of the stars are located. Only the light from the brightest galaxies (on top) makes it all the way to Earth (on the left); The fainter galaxies (the lower two) are either too far away or not luminous enough to be seen by our telescopes on Earth. Such faint galaxies might therefore go completely unnoticed!

In the middle of the figure to the right, I've added two quasars. A quasar is a super luminous object which shines so bright that the light can be seen billions of lightyears away. These very small and super luminous sources are the perfect background sources to identify the absorbing gas in galaxies. The sightline to quasar A passes through the faint galaxy in the foreground and has some of its light absorbed away. This tells us that a galaxy is located in front of quasar A.

Quasar B on the other hand is shining straight down to Earth without any galaxies along the line of sight. By comparing the number of quasars with and without absorption, we can then measure the amount of gas in galaxies on average, and we can identify lots of galaxies that would otherwise never have been within reach — even using our most powerful telescopes.

My latest paper is an attempt to model the number of such sightlines with absorption. We try to come up with a representation of how the gas is distributed inside and around galaxies, and we then compare how many absorption sightlines we should see compared to unabsorbed sightlines. For the first time, our new model is able to reproduce the counting statistics for the very dense gas in galaxies. This is the kind of gas that is on the brink of forming the next generation of stars in those distant galaxies.

Being able to model this important gas phase brings us one step closer to understanding how galaxies evolve over time. And in the near future, we will be able to refine this model thanks to breathtakingly large surveys at some of the leading observatories in the world. I can't wait to see what we'll learn from all those data!

The article is published in the scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics

Also available for free at arXiv.org.